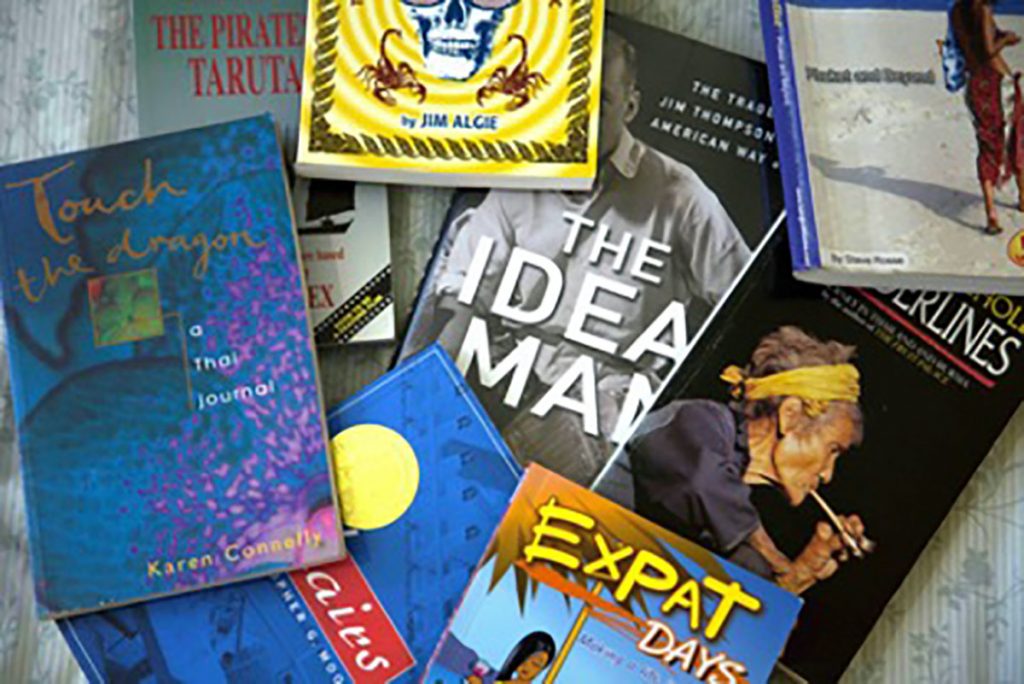

While waiting for Covid19 to go get lost, the blog’s longtime correspondent John Borthwick re-visits Thailand via some of the best writing about the Kingdom.

Thailand has been celebrated in many genres of literature from fiction and fantasy to poetry, non-fiction and sci-fi, so let’s armchair travel a few of them.

Through Thai Eyes

Jasmine Nights is a magical and poignant novel by Thai author and musical composer S.P Somtow. His semi-autobiographical romp is hailed as “the classic coming-of-age tale in Thailand of the 1960s.” Set in his aristocratic family’s time-warp enclave (“our remote little island kingdom on Sukhumvit Road”) the tale is alive with eccentric aunts, suitors, princelings and a pet chameleon. And then add sex, politics and farce.

Pira Sudham writes acclaimed novels and short stories about ordinary Thai life — no bars, spas, wannabes or five swizzle-stick resorts here — usually among the poor rural regions of Isaan, north-eastern Thailand. His best-known work Monsoon Country follows a farmer’s son journey to Bangkok and then as an overseas scholarship student — paralleling Sudham’s own path. Look too for his short story anthology It is the People.

Thailand‘s much-loved royal poet Sunthorn Phu (1786—1855) led a life of romance, scandal and banishment that is mirrored in his own works. As “the People’s Poet of Thailand” he has been compared to Shakespeare in the range and national importance of his works. His poetic saga Phra Aphai Mani traces a Byronic hero’s romantic adventures in ancient Siam. Koh Samed is the setting for one tale of a lovesick mermaid and exiled prince, which is commemorated today in the statues of the lovers on the island’s Sai Kaew Beach. Not far from Samed you can also visit the Sunthorn Phu Memorial Park in Klaeng, Ranong Province.

A Fictional Land of Smiles

Ex-Hong Kong lawyer John Burdett has written six best-selling Thailand crime novels featuring his eccentric Thai-farang police detective Sonchai Jitpleecheep. Set mostly in a Bangkok of dirty politics, bizarre murders and sometimes equally bizarre sex, these street-smart page-turners are full of gloriously bent characters, hungry ghosts and dark shots of comic relief. Start with Bangkok 8 and binge on.

Burdett’s cast of good- and evildoers is more nuanced than the penny dreadful dames and private dicks in the prolific Christopher G. Moore’s Bangkok novels. His who-dunnits like the popular Killing Smile trilogy are set in a city that seems to consist predominantly of bars and illumination by red lights. Alternatively, his short story collection Chairs isrecommended.

“Thailand is the Italy of Asia. Great food, beautiful women, joyously corrupt and totally dysfunctional,” says Jake Needham, author of half a dozen taut, intelligent thrillers set in Thailand. The Big Mango, A World of Trouble and Killing Plato are perfect stuck-in-the-airport novels. His well-informed plots are steeped in international politics, big money bastardry and the onion layers of pan-Asian corruption. (The Wall Street Journal Asianotes, “Mr. Needham seems to know rather more than one ought about these things.”) Plenty of sharp dialogue and always a rattling good pace. Needham’s work is notches above much farang-written Thailand fiction that typically comes with a G-Rating: gumshoes, girls, guns and goons.

Best-selling Nordic noir superstar Jo Nesbo penned a Bangkok crime tale way back in 1998 that was only much later translated to English. Cockroaches sees his Oslo police detective-defective Harry Hole in Bangkok investigating the murder of the Norwegian ambassador who has turned up dead in a seedy motel. As they do. Go-go bars, temples and opium dens are the by-now clichéd backdrops to Harry’s hunt.

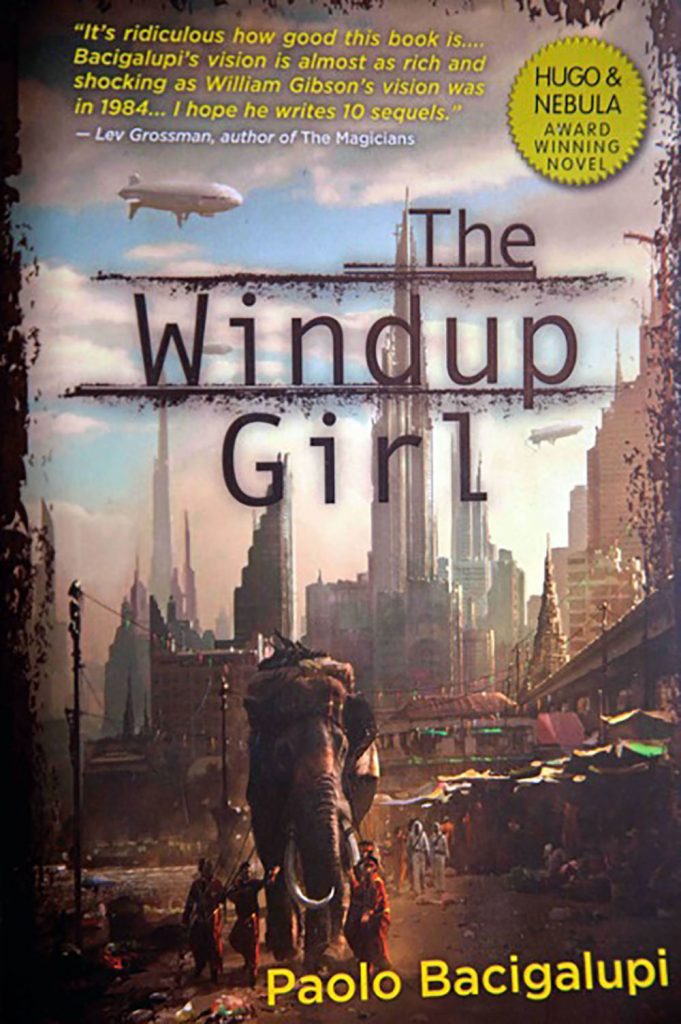

The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi is a cyberpunk science fiction tale of gene thieves, agro-corp wickedness and a beautiful, quasi-human woman, the “windup girl” of the title. All struggling in a future, post-apocalypse Bangkok where heavily armed government departments go to war against each other. Imagine William Gibson’s Neuromancer meets Blade Runner during a GM-induced famine…

Alex Garland’s 1996 novel The Beach needs little introduction, having morphed into a 2000 Hollywood movie that then inspired cycles of devastation-by-visitation on Koh Phi Phi Leh’s formerly edenic Maya Bay. Set on a generic island (in the Gulf of Thailand, but could be anywhere), a tribe of backpackers sees their feral heaven crash to a tropical purgatory as events go troppo, psycho and then kaput! The novelhas been accurately dubbed “the Lord of the Flies for Gen X”.

Behind the Night Bazaar by Angela Savage partly subverts the paradigm, as they say, of male derring-do (or being done-to) in Thailand by at least having a female protagonist and with the action set in Chiang Mai rather than Bangkok. Savage’s private investigator is a 30-ish Australian woman facing the sometimes-comical challenge of “working undercover in a place where she can do anything but blend in.” That place is, of course, a world of murder, bent cops and exploitation.

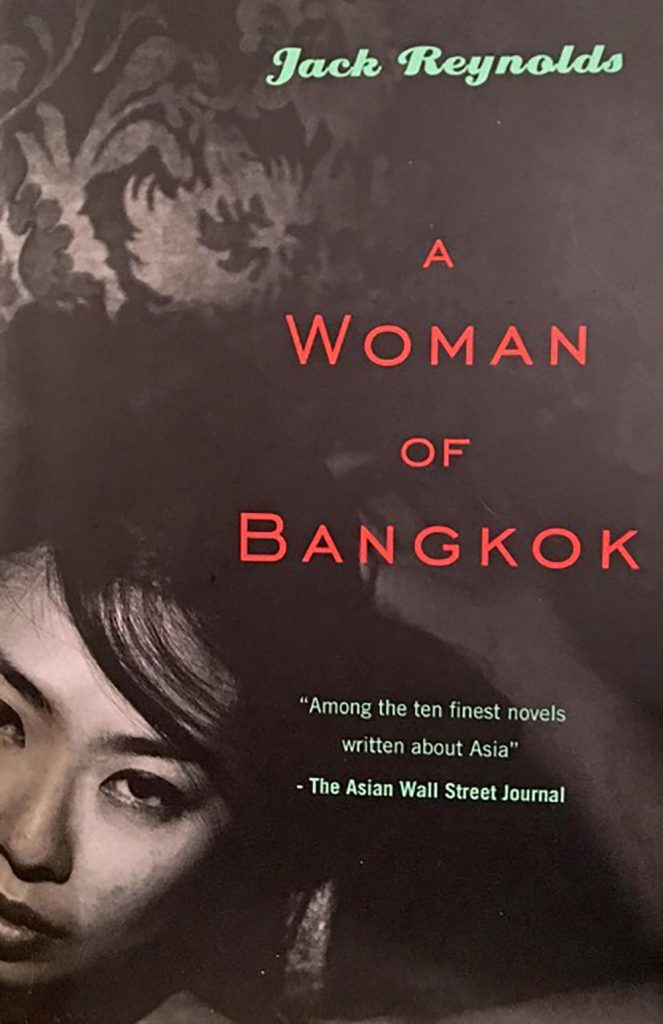

When A Woman of Bangkok by Jack Reynolds appeared in 1956 the Asian Wall Street Journal reviewed it rather generously as “Among the ten finest novels written about Asia.” That’s a big call for the yarn of naïve Western male meets unscrupulous foreign temptress. “Love in vain” is a familiar literary trope played out to this day (and night) in much Thai-focussed, farang-penned pulp fiction; not to mention in real life — which partly explains this compelling novel’s on-going popularity.

Private Dancer sees veteran Irish crime writer Stephen Leather (or at least his tragic young protagonist, Pete) tread the same Bangkok sois, shed the same tears and not learn the same lessons that Jack Reynold’s callow hero didn’t learn 50 years earlier. By the 21st century, however, everything in the Big Mango’s bar world is harder and far more sinister. Poor love-struck Pete sinks deeper into obsession with a lisssom but faithless femme fatale. “Slow Learner”could be his epitaph as well as Leather’s alternative book title.

First-Personally

Canadian poet-novelist-travel writer Karen Connelly knows the kingdom and its language far better than most non-Thai authors. She skips completely the template of “Thailand = erotica + exotica” by looking and living well beyond the neon demi-monde. Try her adroit, youthful account of her exchange student year in Touch the Dragon: A Thai journal. A much later book, Burmese Lessons: A true love story is a gritty, open-heart account of her journey and love relationshsip in the northern Thai jungles amid exiled Burmese resistance groups.

On a much lighter note, expat Australian humorist Neil Hutchison’s cautionary anecdotes about foreigners looking for love in all the wrong Thai places — and yet somehow, sometimes finding it — should be mandatory in-flight reading for all in-bound males between the ages of puberty and senility. Hutcho shares his own hard-won observations of the farang-out-of-his-depth in wry titles such as A Fool in Paradise and Money Number One: The single man’s survival guide to Pattaya.

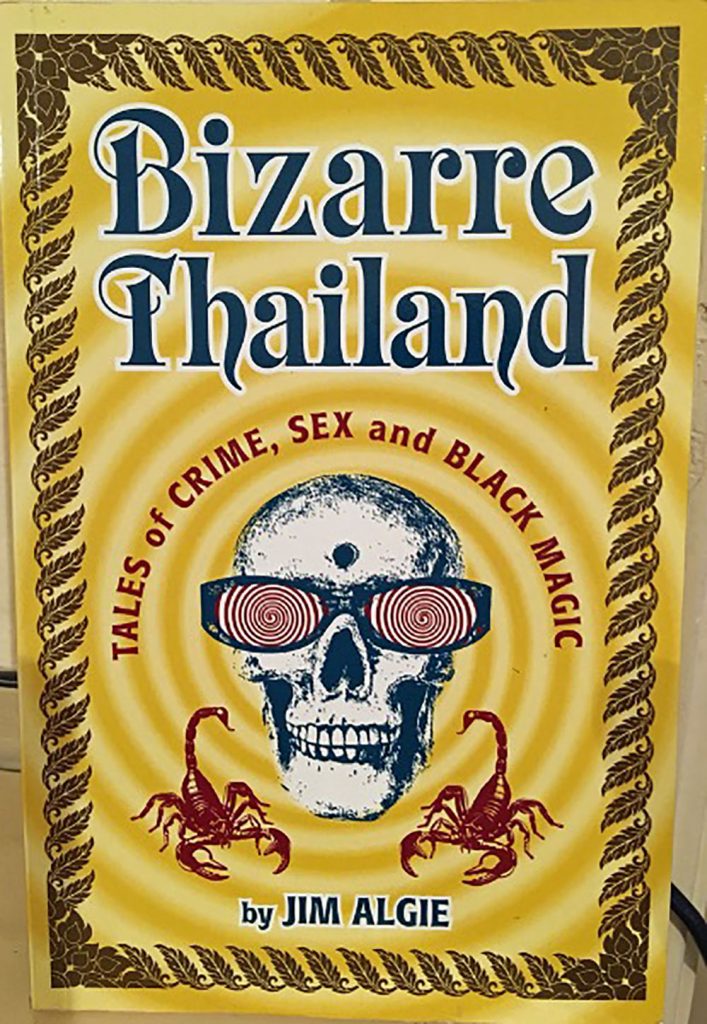

Scottish-Canadian expat Jim Algie’s journalistic explorations in Bizarre Thailand are not as kinky as the book’s click-bait tagline (“Tales of crime, sex and black magic”) might suggest. It’s full of arcane local knowledge about fertility shrines, errant monks and still pervasive Thai beliefs in superstition and magic. Funny too. In a similar but more character-focused vein, also check out two well-made books by another long-time expat writer (and acclaimed biographer of Jim Morrison), American Jerry Hopkins: Bangkok Babylon and Thailand Confidential.

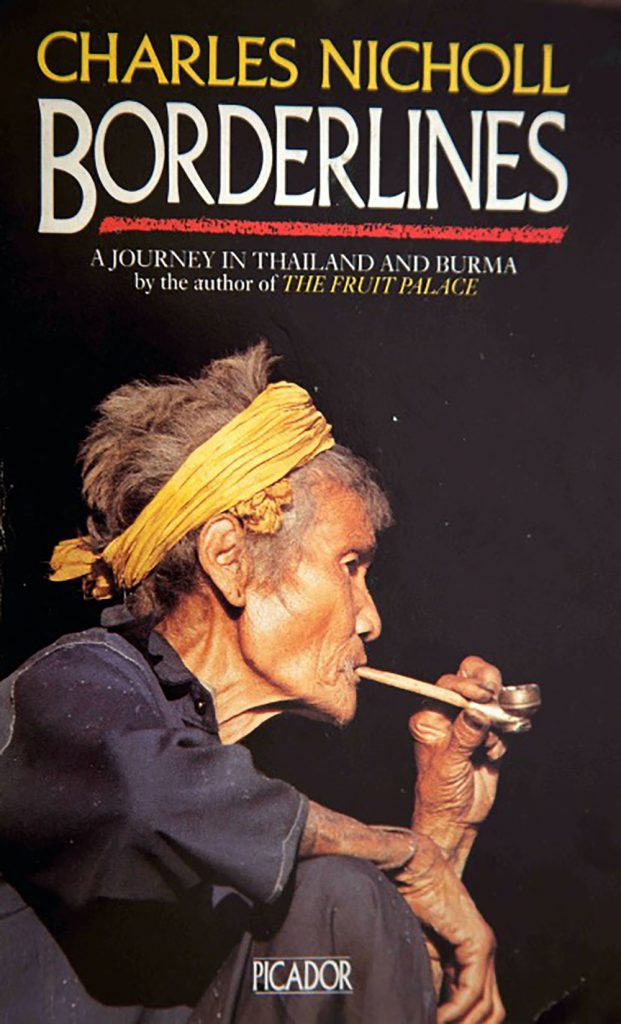

In his travel book Borderlines fine English writer Charles Nicholl heads north to the Golden Triangle and then Burma in search of rebels, jade, opium traders, insights and an elusive Thai friend, Katai: “Sometimes I think that it wasn’t just Katai who ‘got away’, but Thailand itself, the whole strange trip. I never really got to know where I was going, never reached my destination. Perhaps the code of the road is as simple as that. You never do get there. There is just the road, and what it reveals along the way.” Sounds familiar?

The Non-Fiction Kingdom

The Ideal Man: The tragedy of Jim Thompson and the American way of war by American Joshua Kurlantzick is a highly readable biography of the legendary Jim Thompson, the so-called “silk king”, whose crowded career(s) included soldier, spy, socialite and entrepreneur — and ultimately, disappearing man. The book’s sub-title indicates the wider context of Southeast Asian military-political affairs. The result is an informed portrait of one of the country’s most intriguing foreign players as seen against the backdrop of post–WWII Thailand’s turbulent governance.

Journalist Paul M. Handley’s unauthorised 2006 biography of the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej, The King Never Smiles is banned in Thailand but easily available in Cambodia. The author takes an unflinching look at the career of King Rama IX, the world’s longest-serving monarch (from 1946 to 2016). It’s an iconoclastic perspective on the underpinnings and achievements of the king’s reign and of Thailand’s shape-shifting democracy.

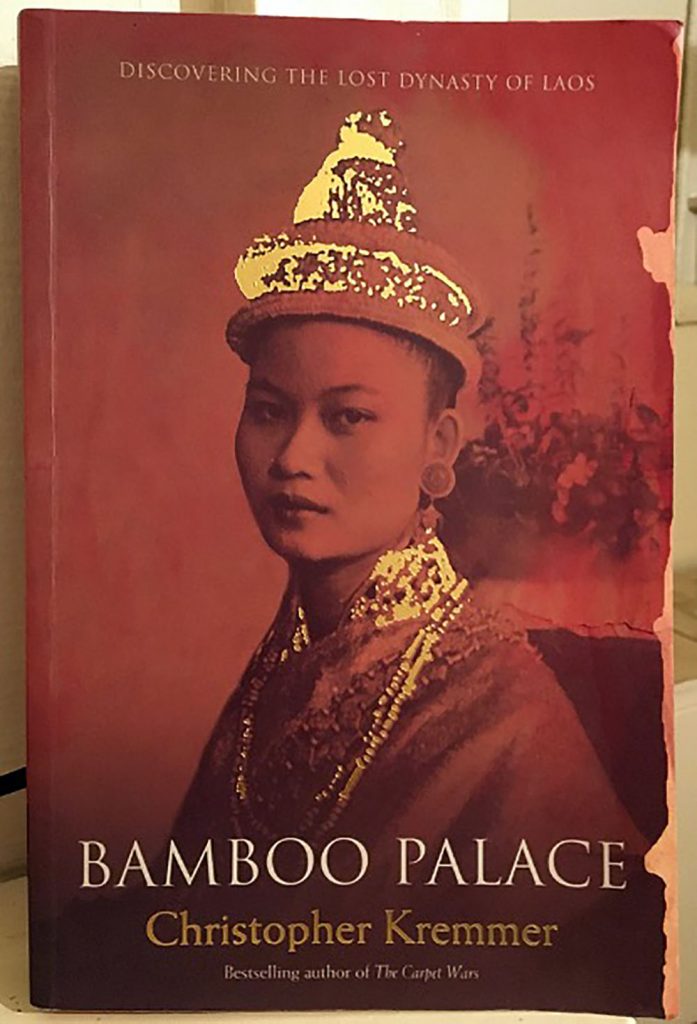

While you’re in the region, Thailand’s next-door neighbour Laos makes similarly fascinating reading. Recommended are journalist Christopher Kremmer’s investigative travels to successfully discover the fate of the last king of Laos, Sisavang Vatthana who disappeared in 1975: Stalking the Elephant Kings and The Bamboo Palace: Discovering the lost dynasty of Laos.

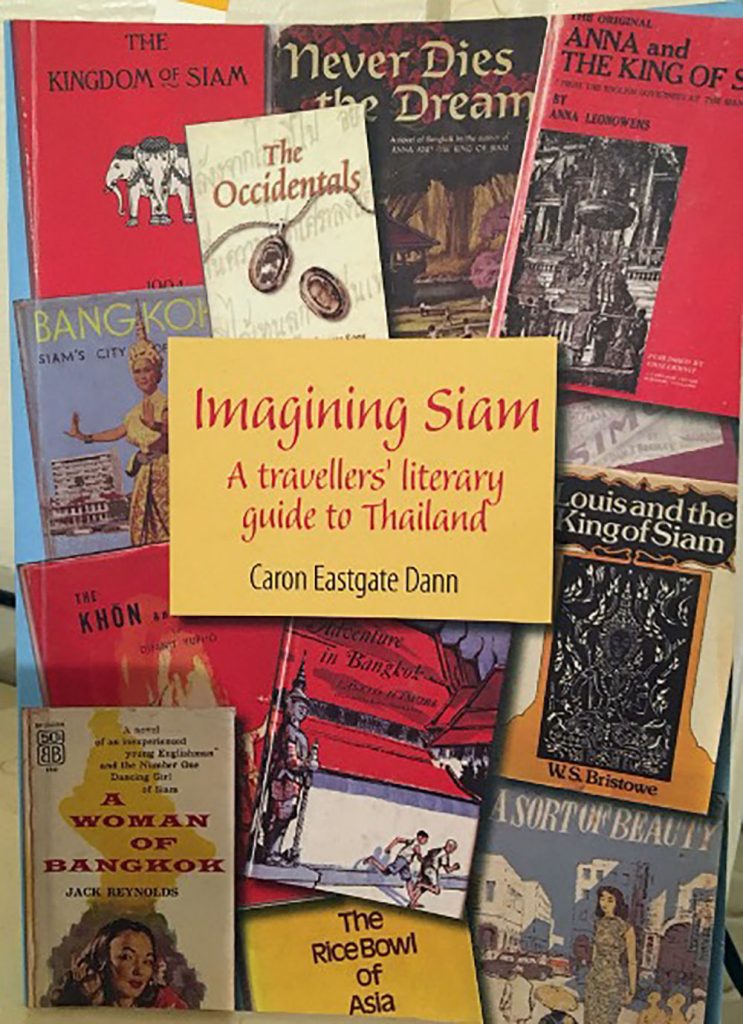

Some of the above titles are out of print but most can be found online or as e-books. For a scholarly perspective on it all, see Imagining Siam: A travellers’ literary guide to Thailand by Dr Caron Eastgate Dann.

Happy reading!